The private life of Pompeii

Unexceptional small towns, lying not far apart, they were stopped in their tracks by a ferocious volcanic episode lasting little more than 24 hours. The date was AD 79, and the event, the eruption of Vesuvius.

Pompeii spreads out in front of you, with its networks of streets bordered by ruined stubs of houses, leading to the public buildings and beyond, out into the countryside and, eventually, the volcano. This place was wrecked, not by streams of hot lava, but by the sheer weight of material that rained down over several hours. Then, when the immense volcanic cloud overhead collapsed, it sent out pyroclastic surges, like a huge blowtorch, belching ash and gas at stupendously high temperatures and moving at extraordinary speed. Herculaneum was instantly incinerated, buried under debris five times deeper than Pompeii.

Clockwise from left: sea creatures mosaic; present-day Herculaneum; marble wall showing Bacchus, Herculaneum

Clockwise from left: sea creatures mosaic; present-day Herculaneum; marble wall showing Bacchus, HerculaneumAt Herculaneum, you look down into tightly packed, narrow streets where most of the houses (and shops) rise almost full height. It looks much more like a town than Pompeii, even though it lies 75ft down in a virtual quarry, consisting of the detritus from which it was, eventually, extracted. Here Vesuvius stands ominously close, like a painted stage set, changing colour and visibility according to the weather, light and season. In the intervening two millennia of volcanic action, it’s changed shape, too.

No wonder the mountain exerts such fascination, having drawn innumerable generations of visitors up to its rim, all of them wondering when it might next erupt. It’s been painted, photographed and filmed, written about, sung about and reconstructed – from London to Las Vegas – a phenomenon I explored in my book, Vesuvius: The Most Famous Volcano In The World.

Volcanic activity remains essentially unpredictable and for all the scientists, seismologists and geologists who study it, those who live close to Vesuvius (even, once again, on its actual slopes) are as oblivious to the dangers of another bout of activity as their 17th-century ancestors, who pinned their faith on the miracles of the patron saint of Naples, St Januarius.

TOWNS OF WEALTH

In the new British Museum exhibition the emphasis is on life, rather than death, in Pompeii and Herculaneum. It includes a marble panel showing the earthquake that shook the land six years earlier, a vivid warning of the instability of this of the countryside (ironically, because of volcanic lava). The carving shows the temple keeling over, a donkey’s legs folding beneath it. But no one was there to capture the next natural horror. Life stopped in AD 79, freeze-framed.What slowly began to emerge from the sites, after 1,500 years’ oblivion, was domestic and civic life in two provincial Roman towns.

Evidence comes from stone tablets and wall inscriptions bearing electoral information and boundary markers to property or legal instructions. Many people are revealed, by their names, to be freed slaves, pointing to a surprisingly uid society. Their diet (newly discovered by DNA analysis) and imported foodstu s (preserved by the carbonising heat at Herculaneum) point to widespread wealth, while a liking for ne wine and erotica are evidence of Roman tastes.

The exhibition is based on the layout of a house, room by room. In the bedroom, where small children sleep too, are cosmetic containers, mirrors and jewellery. In the kitchen, there are heaters for food and water, a mould in the shape of a crouching hare and a metal colander that would pass unnoticed (except for its elegant pierced decoration) in a 21st-century house. Less familiar would be the dormouse jar, where the creatures were fattened up until ready for a quick turn in hot oil with seeds and honey, or the household gods and shrines, pointing to a religion practised at home as well as in the temple.

FRESCOES TELL THE STORY

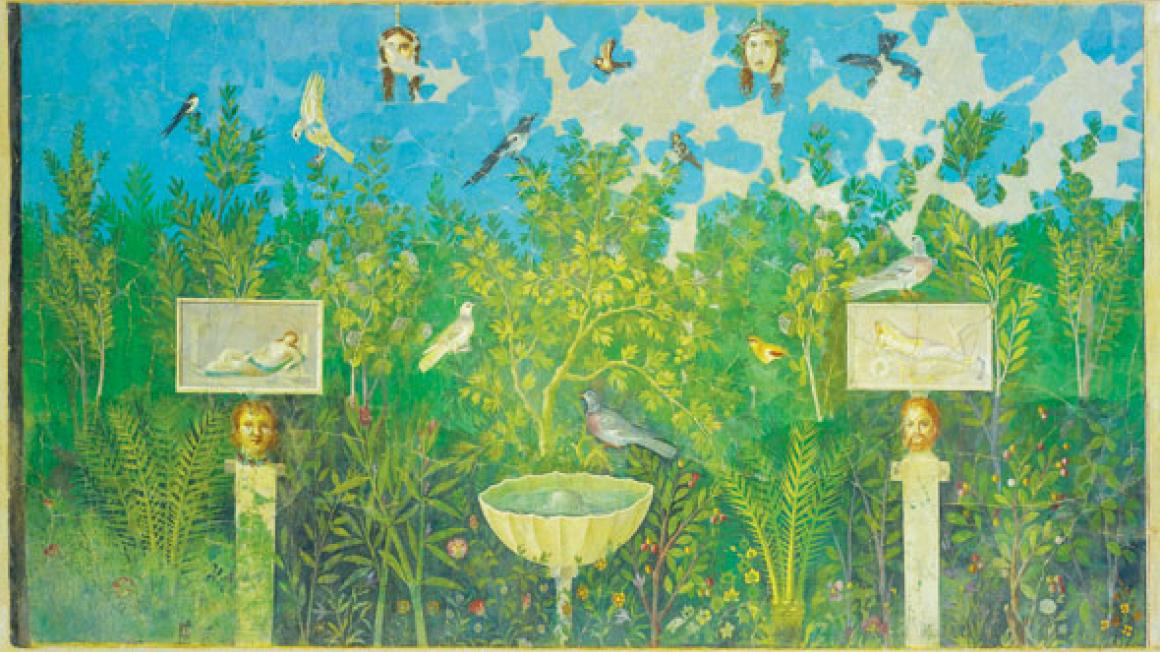

Water flowed along (deadly) lead pipes, portable toilets served their purpose, while in the garden, sundials told the time and fountains spouted from the mouths of ceramic frogs. Pompeiian household decoration seems surprisingly familiar, having been borrowed by 18th-century architects for many splendid neoclassical interiors across Europe. Frescoes convey more about the people and their lives, from the crowd in the baker’s shop to a version of Vesuvius, clad in vines and with Bacchus standing by. One jewel of the exhibition is a room painted as a garden.On that day in August or, more likely, October (a melted metal heater suggests that evening temperatures had dropped) death came by intense heat or su ocation, or both. At Pompeii people were coated in thick ash, forming a kind of plaster cast from which ingenious mid-19th-century archaeologists extracted their tensed forms. In contrast, Herculaneum was buried deep below the massive build-up of material.

A bracelet from Pompeii and a bronze statue from the Villa of the Papyrii, Herculaneum

A bracelet from Pompeii and a bronze statue from the Villa of the Papyrii, HerculaneumHere, surviving artefacts were cooked at 400C, so that everything from the contents of the kitchen cupboard, including imported peppercorns and dtes, to a child's cot and ornamental roof timbers, were carbonised and preserved. Recent nds from Herculaneum’s shoreline, both skeletons and artefacts, can be scienti cally examined with the latest techniques available and so our knowledge grows. Two small ruined towns continue to give an insight into an entire civilisation.

Life And Death In Pompeii And Herculaneum is at the British Museum, London, WC1, until 29 September: 020-7323 8181, www.britishmuseum.org

Pictures: Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei